Definition and Prevalence

- Pruritus is an unpleasant sensation that causes a strong urge to scratch, negatively impacting psychological and physical well-being.

- Chronic pruritus (CP) is defined as an unpleasant sensation resulting in a need to scratch that lasts more than 6 weeks.

- It is one of the major dermatological complaints during pregnancy.

- Recent studies indicate that 18-40% of pregnant patients experience pruritus.

Associated Conditions

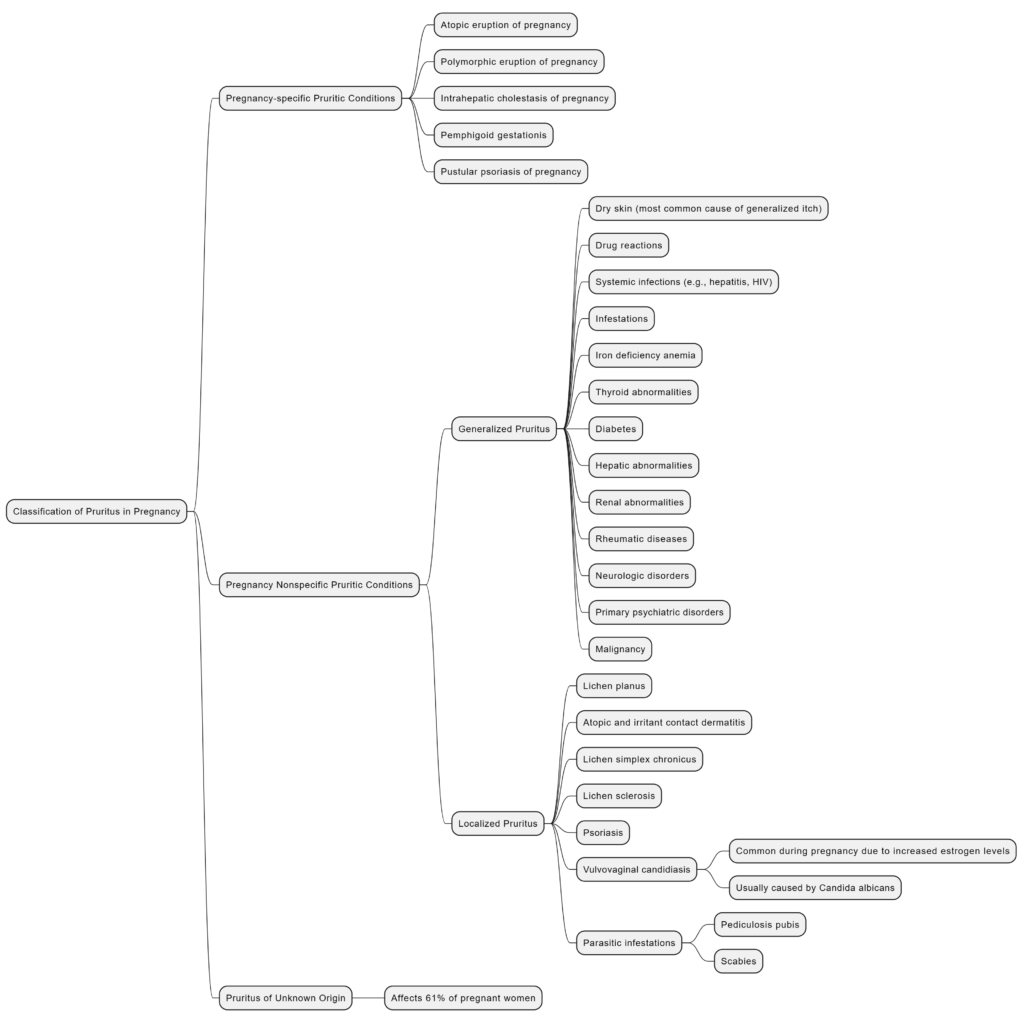

CP can be associated with pregnancy-specific conditions such as:

- Atopic eruption of pregnancy (AEP)

- Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP)

- Pemphigoid gestationis (PG)

- Intrahepatic cholestasis in pregnancy (ICP)

Pruritus may also arise from:

– Dermatoses coincidentally developing during pregnancy

– Exacerbation of preexisting dermatoses

– Physiological skin changes in pregnancy

Pregnancy-specific conditions

Atopic Eruption of Pregnancy (AEP)

Definition and Introduction

- In 2005, Ambros-Rudolph et al. introduced AEP as an umbrella term for benign pruritic disorders of pregnancy.

- AEP includes conditions previously diagnosed as eczema of pregnancy, prurigo of pregnancy, and pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy.

Epidemiology

- AEP is the most common dermatosis of pregnancy.

- AEP encompasses:

- Patients with exacerbation of preexisting atopic dermatitis (approximately 20% of cases).

- Patients experiencing skin manifestations for the first time during pregnancy.

Risk Factors

- Patients with a family history of atopic dermatitis are at increased risk of developing AEP.

- The disease is often idiopathic, occurring without a known cause.

Types of AEP

- E-type (Eczematous):

- Classical distribution of lesions.

- Eczematous eruption on the face, neck, pre-sternal region, and flexure sides.

- P-type (Prurigo):

- Presence of small, pruritic, erythematous, often grouped papules.

- Predominantly on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and the trunk.

Coexistence and Generalization:

- E and P types often coexist.

- Lesions can generalize.

- Secondary lesions include excoriations from scratching and bacterial or viral superinfection (e.g., eczema herpeticum).

Diagnostic Workup

Medical History and Examination:

- Detailed medical history.

- Comprehensive dermatological examination of the entire skin, including mucosae.

Clinical Presentation:

- Early onset of eczematous/prurigo skin lesions (before the third trimester).

- Involvement of the trunk and limbs.

- Possible atopic family or personal background.

Histopathology:

- Nonspecific and varies with clinical type and stage.

- Skin biopsy is not indicated for diagnosis but may help exclude other causes of pruritus.

Immunofluorescence:

- Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) and indirect immunofluorescence results are negative.

Laboratory Tests:

- Elevated serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels in about 30–70% of cases.

- The role of IgE levels as a diagnostic criterion is unclear.

Allergy Tests:

- Prick and patch tests are not recommended during pregnancy.

Treatment

Patient Education:

- Emphasis on sufficient emollient therapy as basic dermatological care.

- Various compounds were studied for their contribution to skin hydration and reduction in pruritus.

Second-line Treatment for Mild and Moderate AEP:

- Topical Glucocorticosteroids:

- Used to manage mild and moderate AEP.

- Systemic Antihistamines:

- Recommended alongside topical treatments.

- Narrowband Ultraviolet B (UVB):

- Recommended for moderate and severe AEP, especially in early pregnancy.

- Second-line Treatment for Severe AEP:

- Systemic Glucocorticosteroids:

- Short-term use for recalcitrant pruritus.

- Prednisolone dosage: 0.5–2 mg/kg/day.

- Immunosuppressive Agents:

- Considered for severe cases unresponsive to phototherapy.

- Cyclosporine or Azathioprine:

- Introduced with caution, weighing risks and benefits.

- Azathioprine may be used off-label if other therapies fail or cyclosporine is contraindicated.

Potential Future Therapy Option:

- Dupilumab:

- Anti-interleukin-4 receptor (IL-4R)-α antibody.

- Inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, affecting various immune cells.

- Promising safety profile in case reports, but more evidence needed.

- Recommended to postpone use in pregnancy until more data is available.

Prognosis and Fetal Risks

Reassurance:

- Excellent prognosis for AEP.

- Not associated with adverse fetal outcomes.

Potential Predisposition:

- Children might be predisposed to atopic eczema based on their parents’ atopic background.

- The disease may recur in subsequent pregnancies.

Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy (PEP)

Definition and Epidemiology

- Also known as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy(PUPPP).

- Benign, self-limiting pruritic inflammatory disorder.

- Incidence: 1 in 120 to 1 in 300 pregnancies.

- Typically occurs in the third trimester or immediately postpartum (about 15% of cases).

- Risk factors include:

- First pregnancy (primigravida)

- Excessive maternal weight gain

- Multiple pregnancies

Pathophysiology and Clinical Characteristics

Theories of Pathogenesis

- Skin stretching in the third trimester or over multiple pregnancies may activate dermal nerve endings, leading to pruritus.

- Possible damage to collagen fibers may induce an allergic-type response, contributing to PEP lesions.

Clinical Presentation

- Polymorphic skin lesions: highly pruritic urticarial papules coalescing into plaques.

- Small vesicles (1–2 mm) without bullae.

- Widespread non-urticated erythema, targetoid, and eczematous lesions.

- Generally spares the periumbilical region, this helps to differentiate PUPPP from PG.

- Lesions often start in the abdominal region within striae distensae and spread to thighs, buttocks, and trunk; distal extremity involvement is rare.

Diagnostic Workup

Diagnosis

- Based on clinical presentation.

- No characteristic histological or immunofluorescence findings.

- Prolonged follow-up is recommended to distinguish from pre-bullous pemphigoid gestationis (PG).

- Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) may be performed if there is clinical uncertainty to rule out pre-bullous PG.

Treatment

First-line Treatments

- Emollients

- Antihistamines

- Topical glucocorticosteroids

Severe Cases

- Systemic prednisolone may be considered if the disease is extensive and pruritus does not resolve.

Spontaneous Resolution

- The disease typically resolves within 4–6 weeks, independent of delivery.

Prognosis and Fetal Risks

Prognosis

- PEP is a self-limiting disorder.

- Does not affect the prognosis for the fetus or the pregnant patient.

Recurrence

- Rare, usually occurs only in first pregnancies.

Pemphigoid Gestationis (PG)

Definition and Epidemiology

- Also known as herpes gestationis.

- Rare self-limited pregnancy-associated bullous autoimmune disease.

- Incidence: Approximately 1 in 2000 to 1 in 60,000 pregnancies.

- Typically occurs in late third trimester but can develop at any time during pregnancy or immediately postpartum.

- Recent reports indicate its occurrence in egg donation pregnancies and rarely in association with trophoblastic tumors.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Characteristics

Pathogenesis

- Similar to bullous pemphigoid with autoantibodies (IgG1 subclass) against bullous pemphigoid antigen 180 (BP180).

- Autoimmunity primarily targets placental proteins, leading to cross-reaction with skin BP180-2 proteins.

- Results in complement activation, eosinophil recruitment, and blister formation at the dermoepidermal junction.

Clinical Presentation

- Initial severe pruritus followed by polymorphic inflammatory skin lesions.

- Erythematous urticarial papules and plaques, often periumbilical, spreading to the abdomen, extremities, and mucosal membranes.

- Progression to tense blisters resembling bullous pemphigoid.

Diagnostic Workup

Diagnosis

- Based on clinical presentation.

- Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows linear C3 and/or IgG deposits along the dermo-epidermal junction.

- Histology is nonspecific; biopsy may be performed to exclude other dermatoses.

- Complement-binding tests like ELISA for circulating IgG antibodies against BP180 may be used.

Treatment

First-line Treatments

- High-potency topical glucocorticosteroids and antihistamines to reduce pruritus and prevent blister formation.

- Non-fluorinated topical glucocorticosteroids preferred for less systemic absorption and fewer side effects.

Second-line Treatments

- Short courses of systemic prednisolone if topical treatments are inadequate.

- Other agents like calcineurin inhibitors, intravenous immunoglobulins, dapsone, and azathioprine are considered if refractory to steroids.

- Rituximab before conception may prevent recurrence in subsequent pregnancies.

Prognosis and Fetal Risks

Fetal Prognosis

- Relatively good, but risks include preterm labor and intrauterine growth retardation.

- Risks are likely linked to disease severity rather than treatment.

Association with Other Autoimmune Disorders

- Increased risk of autoimmune disorders in pregnant patients, especially Graves disease.

Recurrence in Subsequent Pregnancies

- Common, with earlier onset and more severe forms reported.

Intrahepatic Cholestasis in Pregnancy (ICP)

Definition and Epidemiology

- Liver disorder unique to pregnancy.

- Incidence: 0.3–5.6%, with ethnic, geographic, and seasonal variations.

- Striking geographic variation, with higher incidence in certain populations, such as Araucanian Indians (up to 28%).

- Mutations of ABCB4 (MDR3) implicated in biliary secretion of phospholipids may contribute to ICP.

- Associated diseases: gallstones, hepatitis C infection, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes.

- Characterized by inability to excrete bile salts from the liver, leading to increased serum bile acid concentration and pruritus.

- Typically occurs in the second and third trimesters (>30th week), but earlier onset has been reported sporadically.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Characteristics

Reversible Cholestasis

- Due to impaired excretion of bile salts from the liver.

- Increased serum bile acid concentration leads to pruritus, possibly due to increased availability of brain opiate receptors.

- Negative impact on fetal prognosis.

Etiopathogenetic Factors

- Genetic alterations in hepatobiliary transport proteins.

- Hormonal influences, particularly estrogen levels.

- Environmental factors like seasonal variability and diet.

- Potential role of gut microbiota alterations and long-term therapy with vaginal progesterone preparations.

Clinical Triad

- Severe pruritus, jaundice starting 2–4 weeks after pruritus onset, and elevated bile acids.

- Elevated serum bile acids (>10 μmol/l) and abnormal liver function, mainly serum transaminases.

- Jaundice is not always present, reported in only about 10% of patients.

- Pruritus typically begins on palms and soles, and may become generalized, without primary skin lesions.

- Pruritus may worsen with pregnancy progression, other symptoms include steatorrhea and dark urine.

- Steatorrhea may lead to vitamin K deficiency, requiring careful monitoring of prothrombin time.

Diagnostic Workup

Diagnosis

- Based on clinical presentation and laboratory tests.

- Elevated levels of total serum bile acids are a key indicator.

- Liver function tests may show elevated transaminases.

- Other tests may be performed to rule out associated diseases, such as hepatitis C infection.

Exclusion of Other Conditions

- Exclusion of other cholestatic and hepatic diseases.

- Serum bile acid levels >10 μmol/l.

- Mild elevations in liver transaminases.

- Ultrasound and serologic tests to rule out other potential causes.

- Diagnosis based on characteristic symptoms and increased total serum bile acid levels.

Treatment

First-line Treatments

- Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is the mainstay of treatment, reducing serum bile acid levels and relieving pruritus.

- Close monitoring of maternal and fetal well-being is essential.

- Delivery may be considered if maternal or fetal complications arise or if the condition worsens despite treatment.

Spontaneous Resolution

- The disease typically resolves within 6 weeks after delivery.

Additional Treatments

- Primary goal: Reduce serum bile acid levels to alleviate symptoms and decrease fetal risks.

- First-line treatment: Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) 15 mg/kg/day or 1 g daily is administered until delivery.

- Consideration of rifampicin synergistic effect in severe cases (>100 µmol/l) if no improvement with UDCA alone.

- Elective delivery after gestation week 37, especially if bile acid concentrations are >100 mmol/l.

Prognosis and Fetal Risks

Prognosis

- Reversible condition with favorable prognosis for both mother and fetus with appropriate management.

- Risks include preterm birth, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, fetal distress, and stillbirth, particularly in severe cases or if untreated.

- Increased vigilance and regular monitoring are necessary to mitigate potential risks to both mother and baby.

Associated Fetal Complications

- Perinatal mortality, stillbirths, low birth weight, preterm birth, and fetal distress during labor.

General Considerations for Pharmacological Treatment of Chronic Pruritus During Pregnancy

Topical Treatment

- Glucocorticosteroids:

- First-line treatment for CP with inflammatory skin lesions.

- Commonly used: Low- or moderate-potency (e.g., methylprednisolone aceponate).

- Safe: No causal associations with pregnancy outcomes for low- or moderate-potency topical glucocorticosteroids.

- Caution: Excessive use of potent/very potent steroids (>300 g during pregnancy) may risk low birth weight.

- Calcineurin Inhibitors:

- Alternative if steroids are contraindicated/refused.

- Usage: Small areas only, max 5 g/day for 2–3 weeks or as needed.

Systemic Treatment

- Antihistamine Drugs:

- Early Pregnancy: First-generation H1 antihistamine chlorpheniramine (FDA pregnancy category B).

- From Second Trimester: Second-generation antihistamines like loratadine, cetirizine, levocetirizine (FDA pregnancy category B), and fexofenadine (FDA pregnancy category C).

- Phototherapy:

- Narrowband UVB is safe, especially in early pregnancy.

- Supplement folate to reduce neural tube defect risk.

- Prevent melasma: Facial covering advised.

- Glucocorticosteroids:

- Short-term systemic treatment for severe pruritus.

- Prednisolone is preferred, with caution, especially in the first trimester.

- Other Immunosuppressive Agents:

- Cyclosporine (FDA pregnancy category C) or azathioprine (FDA pregnancy category D) for non-responsive cases.

- Monitor maternal blood pressure and renal function with cyclosporine use.

- Biologics and Small Molecules:

- Omalizumab (FDA pregnancy category B) and dupilumab for refractory cases (limited safety data).

- Dupilumab use should be postponed until more safety data is available.

Pruritus in Pregnancy (Not Specific to Pregnancy)

General Causes of Itching in Pregnancy

- Dry skin (most common cause of generalized itch)

- Renal abnormalities

- Hepatic abnormalities

- Thyroid abnormalities

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Malignancy

- Rheumatic diseases

- Drug reactions

- Diabetes

- Infestations

- Neurologic disorders

- Primary psychiatric disorders

- Systemic infections (e.g., hepatitis, HIV)

Specific Conditions

Atopic Dermatitis

- Chronic inflammatory skin disease

- Associated with skin barrier impairment

- Eczematous lesions and itching

- History of atopy common

Prurigo Nodularis

- Chronic inflammatory skin disease

- Very itchy nodular lesions

- Constant pruritus and scratching

- Unknown pathophysiology

Psoriasis

- Common, long-lasting inflammatory skin disease

- Affects approximately 2% of people

- Red, thick, scaling plaques

- Historically thought not to cause significant itching

- Pruritus commonly affects legs, hands, body, back, and scalp

Notalgia Paresthetica

- Chronic pruritus on the back

- Located lateral to the thoracic spine, interscapular, and paravertebral areas

- Affects women more than men

- Unclear pathogenesis

Other Causes

- Pigmented contact dermatitis

- Pityrosporum folliculitis

- Parapsoriasis

- Neurodermatitis

- Primitive cutaneous amyloidosis

Vulvovaginal Itching

Multiple Etiologies

- Lichen planus

- Atopic and irritant contact dermatitis

- Lichen simplex chronicus

- Lichen sclerosis

- Psoriasis

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

- Common due to increased estrogen levels

- Usually caused by Candida albicans

Parasitic Infestations

- Pediculosis pubis

- Scabies

Lichenoid Vulvar Diseases

Lichen Sclerosis

- Involves vaginal, perineal, and perianal skin

- Rarely seen during pregnancy

Lichen Planus

- Autoimmune disorder

- Causes pain and intense pruritus (affects approximately 1% of the population)

Lichen Simplex Chronicus

- Eczematoid disorder

- Results in repetitive itch-scratch cycle

Pruritus of Unknown Origin

- Affects 61% of pregnant women

References

#Addressing Chronic Pruritus in Pregnancy #Pruritus in Pregnancy